| Wilderness programs such as RedCliff

Ascent are relatively new forms of therapy that have not been

subjected to the same outcome and effectiveness evaluations that have

previously been performed on traditional mental health therapies.

There is a substantial body of literature on how to assess mental

health outcomes and what to expect from various therapies; however,

evaluations of wilderness programs are not a part of that literature.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the RedCliff Program,

independent researchers have completed the first of several

effectiveness studies which can directly answer the following

questions: What percentage of program graduates can demonstrate

significant clinical change? What long term impact does program

participation have on teens who complete the program?

How Was It Done? How Was It Done?

A number of participants of an outdoor therapy program were

identified to provide data for the outcome study. All teens that

started the program within a several week period were included. Parent

reported measures of their teenagers mental health were gathered the

day after their son or daughter was admitted into the program.

Follow-up measures were taken 6 months later. Though most teenagers

completed the program in 5-12 weeks, it was determined that long-term

effectiveness measures would be more representative of long-term

change if the study cohort were to experience several months of

community living after completing the program. Of the original cohort

of 64 sets of parents, 91% completed both the baseline and six-month

measures.

To measure program effectiveness, an

instrument called the Youth Outcome Questionnaire (Y-OQ) was

selected. By definition, the Y-OQ is a parent reported measure of a

wide range of troublesome behaviors, situations, and moods which

commonly apply to troubled teenagers. It has demonstrated validity and

reliability and has shown high clinical sensitivity and specificity.

It is currently used in a variety of therapy settings nationally:

inpatient, residential, outpatient, day treatment, and has become the

"gold standard" for measuring youth mental health outcomes. The

instrument assesses six different sub-scales: psychosomatic,

interpersonal relations, intra-personal, social problems, behavioral

disorders, and critical items (behaviors that require immediate

medical attention ei. hallucinations and suicide). Each of the six

sub-scales are used to calculate a total Y-OQ score.

Lets Put This in

Perspective. Lets Put This in

Perspective.

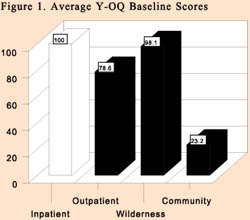

Figure 1 demonstrates the initial baseline Y-OQ scores

which were collected from several inpatient and outpatient programs,

in addition to the wilderness program and teenagers living in the

community. The average wilderness program participant had Y-OQ scores

similar to teens initiating both inpatient and outpatient treatment

programs. As shown, teens living in the community had very low scores

averaging 23.2 points. Due to the value of a standardized instrument,

we are able to compare the level of functioning of youth entering

these different treatment modalities in comparison to the community

norm.

Did the Program Work? Did the Program Work?

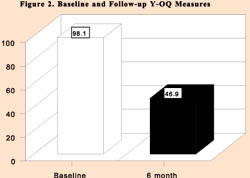

The change in Y-OQ scores that occurred to the average

wilderness program participant from baseline to six-month follow-up is

shown in Figure 2; baseline scores were cut by almost half.

Outcome findings from other mental health therapies have shown that a

13 point decrease in Y-OQ scores is considered reliable and clinically

significant. For the participants in this evaluation, 53 of 58 or

91.4% demonstrated at least a 13 point drop and were considered to

have experienced significant clinical change. Effectiveness

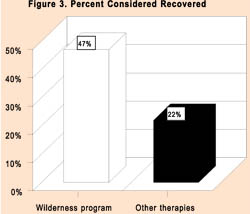

evaluations of other inpatient, residential, and outpatient therapies

have also shown that youth who have follow-up Y-OQ scores at or below

46 can be clinically labeled "recovered". In this wilderness program,

28 of the 58 students or 47% demonstrated Y-OQ follow-up scores of 46

or less. In other words, 47% of the teenagers in this cohort were

considered to be clinically recovered six months after starting the

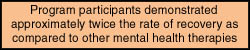

program. How do these rates of recovery compare to recovery rates of

other traditional therapies? Y-OQ data is currently available on the

effectiveness of inpatient, residential, day treatment, and outpatient

settings. In a report that combined the overall results of these

different treatments, researchers reported that each of the therapies

were able to demonstrate some improvement in Y-OQ scores (#4). The

average recovery rate across all of these therapies was approximately

22%. Figure 3 compares the percent of wilderness program

participants who were recovered at six months with the approximate

rate of recovery for other teenagers immediately after completing

non-wilderness type therapies.

Another notable outcome was the unusually

low amount of deterioration which occurred over the six month period.

Reviews of the mental health literature have repeatedly shown that

10-12% of all patients, regardless of whether or not they are

receiving treatment, will deteriorate with time. Based upon this rate

of deterioration, 10-12% of the 58 teenagers (6-7 students) in the

study cohort could normally be expected to worsen during the six

months of the study; however, close inspection of the data revealed

that only two members of the cohort were worse after six months, and

only three failed to demonstrate significant clinical improvements.

This very low level of deterioration is atypical of most mental health

therapies.

Conclusions Conclusions

From this outcome study, it is possible to imply that 91% of

youth who complete the program may expect to experience significant

clinical improvement in mental health status, and almost half may be

fully recovered six months after initiating the program. Because the

study design was not a randomized

clinical trial, it is

impossible to prove that the program is solely responsible for these

improvements in mental health. Despite this limitation, it is obvious

that the program is responsible for most, if not all of the dramatic

improvements demonstrated. clinical trial, it is

impossible to prove that the program is solely responsible for these

improvements in mental health. Despite this limitation, it is obvious

that the program is responsible for most, if not all of the dramatic

improvements demonstrated.

REFERENCES

1. American Professional Credentialing Services LLC, Youth

Outcomes Questionnaire,(1996).

2. Wells, M.G., et al. (1996). Conceptualization and measurement of

patient change during psychotherapy: Development of the Youth and

Adult Outcome Questionnaires, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and

Practice, 33(2),275-283.

3. Tingey, R., et al. (1996). Clinically significant change: Practical

indicators for evaluating psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy

Research, 6(2),144-153.

4. Berrett, K.M., (August, 1998) Youth Outcome Questionnaire (Y-OQ):

Item sensitivity to change. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of

the American Psychological Association. San Francisco, CA.

This research was conducted by Dr. Steven

G. Aldana, a research design specialist and professor in the College

of Health and Human Performance of Brigham Young University. Inquiries

regarding this research may be directed to him by email or phone:

steve_aldana@byu.edu (801)378-2145 |